Featured Scientist:

Leighton W.

Graduate student in Volcanology

Name: Leighton W.

Birthplace: Wellington, New Zealand

Field of Study: Volcanology

Specific research interests: The sounds that volcanoes make

Favorite thing about science: I love watching volcanoes erupt! I enjoy studying earth science as it teaches me about the places where I go hiking and camping.

Fun Facts: Approximately 60 volcanoes erupt world wide every year

Leighton's Science

What can we learn from the sounds generated by volcanoes?

Volcanoes generate a range of sounds: from loud booms due to violent, short-lived explosions to low hums from continuous roiling of lava lakes. By listening to the sounds we can monitor eruptions and learn about volcanoes.

The majority of sounds generated by volcanoes are at a really low pitch and are inaudible to the human ear. Because of this, the sound waves generated by volcanoes are called infrasound (not to be confused with ultrasound that is high pitch above the range of human hearing). By using specially designed microphones we can listen to volcanoes.

A collaborator and I (left) preparing microphones to be deployed at Stromboli volcano, Italy.

Click here to listen to the sounds of a volcano (the sound is normally too low frequency for us to hear so it has been sped up). This recording is from the 2015 eruption of Villarrica (Chile).

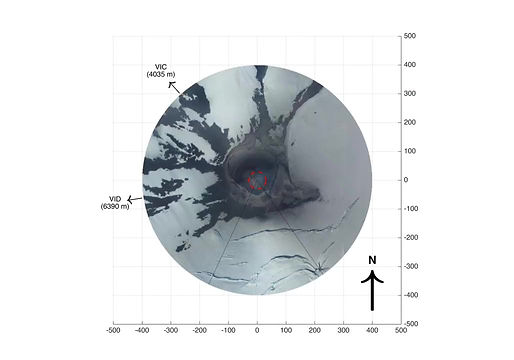

Villarrica is a volcano in Chile with an active lava lake in the crater that erupted explosively on 3 March 2015. Villarrica can be thought of as a giant trombone. Sound is generated by bubbles of gas bursting at the surface of the lava lake. This is similar to how a trombone player makes sound by blowing into the instrument. The pitch of the sound generated by a trombone depends upon the extension of the trombone. If the trombone is extended then the pitch is low. If the trombone is retract then the pitch is high. Similarly, the pitch of the sound generated by Villarrica depends upon the position of the lava lake. If the lake is deep in the crater the pitch is low. If the lava is shallow in the crater the pitch is high.

Volcanoes can be compared to musical instruments. Similarly to how a trumpet and a tuba make different sounds, different volcanoes make different sounds. Furthermore, similar to how a musical instrument can make different sounds a volcano can make different sounds. By listening to the sounds that volcanoes make we can learn about the volcano and state of eruptive activity.

During the several days before the 3 March eruption of Villarrica the pitch of the sound increased. We were able to use computer models to show that the change in pitch was due to the lava lake rising in the crater. This information is extremely useful for monitoring agencies and scientists trying to understand volcanoes. Unfortunately, we were only able to complete this study after the eruption. However, future work monitoring how the pitch of the sound changes may be able to provide real time information about eruptive activity at volcanoes like Villarrica.

To learn more about listening to Villarrica see here for a scientific article or here for the associated press release.

While I do spend most of my time behind a desk working on a computer, I love the opportunity to travel to other countries to do research at volcanoes. Field work is not always comfortable and glamorous but it is always fun!

Base camp by El Reventador (Ecuador)

Observing eruptions at Stromboli (Italy)

I have a lot of questions that I am trying to answer about how volcanoes work and how to better monitor volcanoes by listening to the sounds they make. Some of the questions that drive my research are:

-

What is the shape of a volcano's crater? Does the shape change during an eruption?

-

How much material is erupted from a volcano?

-

Do different eruption styles make different sounds and how can we tell them apart?

Do you have questions about volcanoes? Earth sciences? Being an earth scientist? What it is like to see a volcano erupt? Click below for questions Leighton has answered.

Sped-up video of an eruption of El Reventador volcano (Ecuador). In the foreground is an active lava flow releasing hot gas.